Blogs

April 19, 2023

Making Sense of the Parisian Scooter Ban

Earlier this month, Parisians took to the polls to vote on a referendum about whether to ban shared electric scooters throughout the city. Shared scooters have been available in Paris since 2018, and in those five years the city has become one of the world's largest markets for electric shared mobility. The growth in "micromobility" — the industry term for small vehicles such as electric scooters and bicycles — has coincided with a major overhaul of the city streets, led by Mayor Anne Hidalgo, to take space in city streets from cars and increase designated space and infrastructure for walking, cycling, and transit.

The results of the Paris scooter referendum were decisive: 89% of voters cast their ballots to ban the scooters. However, only 7.5% of eligible voters went to the polls. So starting on September 1, the scooter operators Lime, Dott, and Tier will remove the roughly 15,000 shared rental e-scooters currently operating in the city.

Was this a resounding victory for local democracy and a clear mandate to ban scooters, as Mayor Hidalgo has stated? Or was it instead an effort to avoid making difficult political decisions, as scooter operators or boosters might suggest? These are the two predominant narratives emerging from the vote, but perhaps the answer is deeper and more nuanced. My research on the topic suggests that much of the public discourse around scooters has to do with perceptions, both good and bad, accurate and inaccurate.

Among the reasons that Parisians voted to ban the e-scooters is the fact that many people have a negative perception about them. These negative perceptions stem from the manner in which scooters arrived in cities ("dumping" a large number of scooters on city streets at once), along with continued concerns about vandalism, safety for riders and pedestrians, reckless riding, and parking.

Among these issues, scooter parking has emerged as a persistent and persnickety challenge for cities across the globe. Every city has its own regulations about how to deal with the problem, though these regulations typically vary slightly — what's permitted in one city may not be in another.

Where is scooter parking permitted in U.S. cities? Source: Brown, Anne. 2021. "Micromobility, Macro Goals: Aligning Scooter Parking Policy with Broader City Objectives." Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives 12 (December): 100508. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trip.2021.100508.

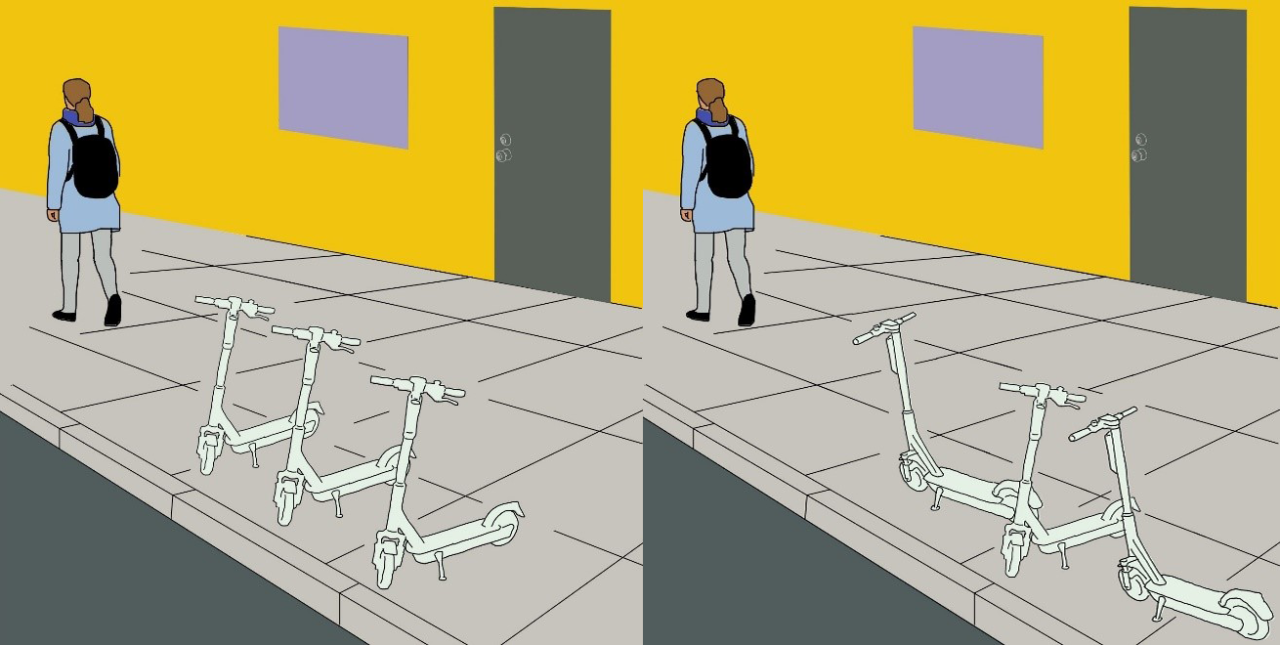

But even when people park their scooters according to what the city permits, pedestrians might not view the scooter as parked properly. In a recent study I published with Anne Brown and Calvin Thigpen, "Clutter and Compliance: Scooter Parking Interventions and Perceptions," we dug into the question of what counts as naughty scooter parking. We found that "public perceptions of improper parking are largely driven by concerns about pedestrian accessibility and an aesthetic sense of tidiness and order." In general, we find that when scooters are parked in a tidy manner (below, left), they are viewed more positively by the public. But when they are untidy, askew, or jumbled (below, right), even if they are not in anyone's way, people viewed them as problematic.

Two scenarios showing scooters parked in compliance with regulations, yet one is perceived to be compliant (left) and the other is viewed as non-compliant (right). Source: Klein, Nicholas, Anne Brown, and Calvin Thigpen. 2023. "Clutter and Compliance: Scooter Parking Interventions and Perceptions." Active Travel Studies 3 (1). https://doi.org/10.16997/ats.1196.

Our deeper look into scooter parking can also help expose a narrow focus on this issue and possible biases. In our earlier research, we also found that cars mispark more often than scooters. However, when we asked planners and the public their perceptions of this problem, they routinely think the opposite is true, that scooter misparking is more common than car misparking. It may be that the newness of scooters is resulting in an instance of salience bias*, and the fact that they are new and noteworthy is attracting outsized attention. For more than one hundred years, cars have been navigating and parking on city streets. Yet even with a century of experience, we have not "solved" the problem of car parking, despite the fact that almost every city has a dedicated staff that regularly patrols city streets looking to fine, tow, and boot those who do not park properly. Further, the problem of car parking is often normalized. It happens so often, most people do not even notice it.

The challenges that Paris encountered are not unique. They are not the first and they probably will not be the last city to ban shared e-scooters. However, for residents, planners, and policy-makers who decide to keep electric scooters, guidance on how to mitigate some of the issues is needed. Based on our research, we suggest that cities with scooters should focus their parking policies to make them simple and intuitive. We should align policies with what the public thinks counts as compliant parking. Our research suggests that this can most effectively be achieved through the installation of physical parking infrastructure that signals to riders and non-riders alike where shared scooters are to be parked.

*Thanks to Pedro Homem de Gouveia of POLIS for this framing.

References

Brown, Anne. 2021. “Micromobility, Macro Goals: Aligning Scooter Parking Policy with Broader City Objectives.” Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives 12 (December): 100508. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trip.2021.100508.

Brown, Anne, Nicholas J. Klein, Calvin Thigpen, and Nicholas Williams. 2020. “Impeding Access: The Frequency and Characteristics of Improper Scooter, Bike, and Car Parking.” Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives 4 (March): 100099. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trip.2020.100099.

Klein, Nicholas, Anne Brown, and Calvin Thigpen. 2023. “Clutter and Compliance: Scooter Parking Interventions and Perceptions.” Active Travel Studies 3 (1). https://doi.org/10.16997/ats.1196.